Collection of Italico Brass, Venice;

Thence by descent, until sold, London, Sotheby’s, 8 July 2021, lot 189, where acquired by the present owner.

Baltimore, Baltimore Museum of Art, From El Greco to Pollock: early and late works by European and American artists, 22 October – 8 December 1968.

A. Ravà, G. B. Piazzetta, Florence 1921, p. 60, photo no. 5;

R. Rearick, in From El Greco to Pollock: early and late works by European and American artists, exh. cat., (ed.) G. Rosenthal, Baltimore 1968, pp. 56-57, cat. no. 37, reproduced in black and white;

L. Moretti, ‘La data degli apostoli della chiesa di San Stae’, Arte Veneta, no. XXVII, 1973, p. 319;

R. Pallucchini & A. Mariuz, L’opera completa del Piazzetta, Milan 1982, p. 84, cat. no. 34, reproduced in black and white on p. 83;

D. Ton, in Tiepolo: Venezia, Milano, l'Europa, exh. cat., (eds.) F. Mazzocca & A. Morandotti, Milan 2020, p. 176, under cat. no. 25.

Click here to download the factsheet

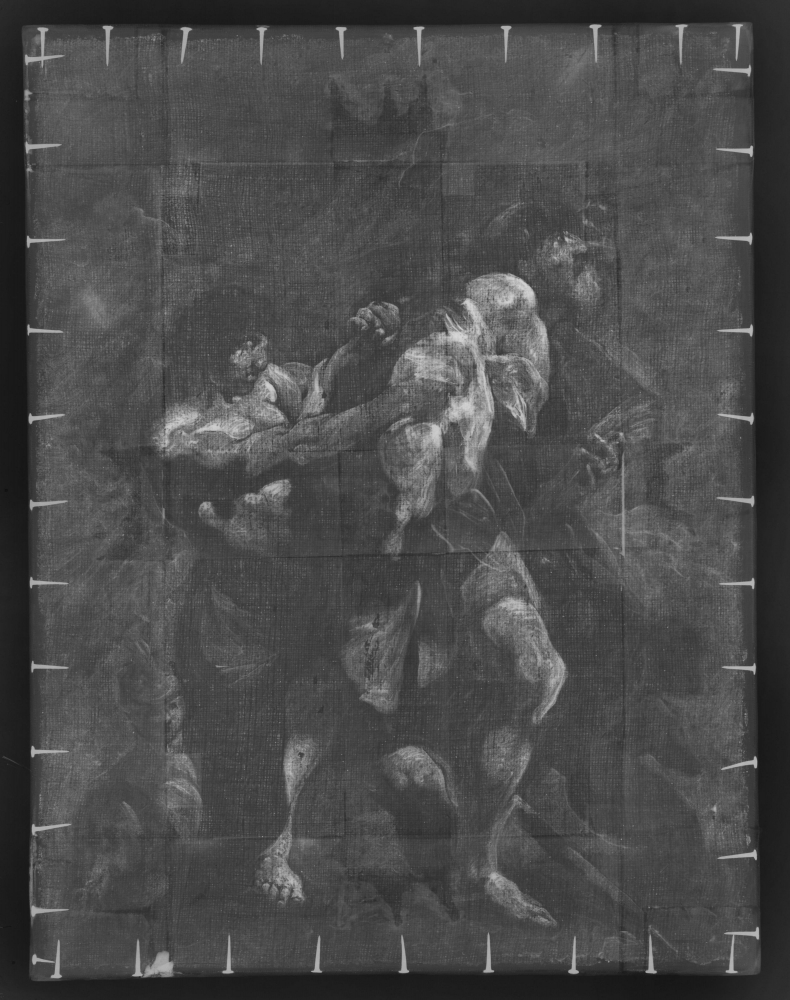

This vigorous and swiftly executed oil sketch is a bozzetto for Piazzetta's Arrest of Saint James, traditionally known as The Martyrdom of Saint James, in the Church of San Stae (Saint Eustace), Venice. In the words of George Knox, this latter painting ‘has long been regarded as one of the masterpieces of Piazzetta and one of his pivotal works.’[i] It is also the first major painting by the artist for which we have more or less complete documentation, thanks to the research of Lino Moretti who discovered and published the contractual documents relating to the commission in 1973.[ii]

The finished painting was part of a cycle of twelve pictures completed between 1722-3, which were commissioned by the nobleman Andrea Stazio from twelve Venetian painters who were each required to depict one episode in the lives of the Apostles.[iii] The iconography was tied in with the architecture of the church, as the will stipulated that the narrative scenes of the twelve apostles would correspond with the 12 columns in the nave of the church.

The terms of the codicil to Stazio’s will makes it clear that by April 1722, ‘two most famous painters’ had agreed on the price and given instructions to enter into agreements with four other painters so that six works could be commissioned simultaneously, and this would then be followed by a second group of six painters. All the artists were required to produce a preliminary oil sketch, or bozzetto, for approval from a small committee comprising representatives of the parish and Stazio’s agent, Michele Priuli, and presumably the ‘two most famous painters’ who had overall artistic control of the project, but Piazzetta’s appears to be the only bozzetto relating to the commission which has survived.[iv] The canvasses themselves were initially destined to hang on the lower part of the columns of the nave, but these were transferred in the second half of the eighteenth century to the choir. The names of the ‘two famous painters’ were not specified, but Leslie Jones’s hypothesis[v] that they were Gregorio Langetti and Sebastiano Ricci, both very well-established artists at the peak of their careers, has generally been accepted by subsequent scholars. They were assigned the two most important apostles – Saint Peter (Ricci) and Saint Paul (Langetti) – while the canvas depicting the crucifixion of Saint Andrew, Stazio’s name saint, was given to Antonio Pellegrini, who, like Ricci, had already established an international reputation.[vi] Jones argues plausibly that the other painters involved in this first phase of the project were Balestra, Piazzetta and Pittoni, and Knox has suggested plausibly that Piazzetta might have had some say in the choice of the saint to whom he was assigned and that the painting might have been conceived in part as a very personal tribute to his father Giacomo, whose name saint was Saint James.

The importance of the commission is underlined by the fact that the artists chosen included some of the leading Venetian painters of the time such as Sebastiano Ricci, then in his early sixties and at the height of his powers, Pittoni, Pellegrini, Piazzetta and Langetti’s former pupil, the young Giambattista Tiepolo, then only in his late twenties but already a rising star, as well as some older and much less well-known painters such as Niccolo Bambini, who was then aged 71 to Tiepolo’s 27. The artists who took part in the commission represented a wide spectrum of contemporary Venetian painting: from the older and more traditional classicising painters such as Antonio Balestra and Gregorio Lazzarini to the grand exponents of the European Rococo Pellegrini and Sebastiano Ricci, the ‘illuministi’ already well-known and sought-after outside Italy who were pioneering the revival of the courtly and light-hearted style of Veronese in Venetian painting.

Piazzetta stood in stark contrast to these last two painters with his brutal realism and sombre, Caravaggesque colouring and deep chiaroscuro. He was one of the last great exponents of tenebrism, orchestrating, in Michael Levey’s words, in contrast to the ‘light chamber music’ of Ricci and Pellegrini, a ‘thundery, assertive, almost growling Baroque cantata for bass voice and brass’[vii]. As Levey observed elsewhere, Piazzetta’s Martyrdom of Saint James ‘makes the work there of the rest of his contemporaries look very slight and artificial’, with the exception, Levey qualified, of ‘the young Tiepolo, who was then briskly and misguidedly aping Piazzetta’s style’.[viii] Whether misguided or not, Tiepolo, who was soon to become the leading European champion of the Venetian Rococo as pioneered by Ricci, was still working at this period in a style imbued with the dark tonalities and chiaroscuro of the Baroque, and his Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew can be seen as a very direct response, or almost a pendant, to Piazzetta’s great canvas of Saint James, from whom it borrows both the strong diagonal and the dramatic placement of the figures against a landscape that falls away sharply in the background. Knox observes that this was a ‘warm tribute’ to the older artist,[ix] though there may have been an element of competitiveness in the young Tiepolo’s canvas which, with its wild gestures and facial expressions, maximises the melodramatic possibilities of the scene.

In both canvasses there is a brutal dynamism and dramatic realism which is totally at odds with the suave and somewhat inconsequential prettiness of the paintings by Pellegrini and Ricci. Compared to Tiepolo’s painting, however, Piazzetta’s is relatively restrained with its subdued colouring and the way in which the figures turn away from, rather than towards, the spectator. The paint is far more thickly applied, particularly in the rendering of Saint James’s sleeve, and the figures have a solidity which perhaps reflect Piazzetta’s early training in his father’s sculpture workshop. Although the painting was traditionally entitled Saint James led to Martyrdom, what we are presented with is in fact a scene of flight and capture – rather ecstatic martyrdom, as is the case with the Tiepolo. The old saint, all too human, tries to make his lumbering escape with his book and his pilgrim’s staff, and is snared with a rope and dragged back by his ruffianly captor. It is a scene of arrest rather than martyrdom, which in the overall scheme of canvasses in San Stae was designed to echo The Arrest of Saint Peter painted by Pietro Uberti, though the source for Piazzetta’s canvas is not the Acts of the Apostles, but the much later medieval Golden Legend. Splendid though Tiepolo’s canvas is, it lacks the stubborn realism of Piazzetta’s Martyrdom in which the plebeian saint and his violent captor are held in a balance of opposing forces. ‘One might not like to think of St James as a dishevelled hobo held by a brutish guard’ wrote Alice Binion, ‘but there is no forgetting the crude pair once it has been seen’.[x]

Piazzetta’s Martyrdom of Saint James is a work of defining importance in his artistic career and the first securely dated painting of which we have reasonably extensive documentation. The artist was already 40 when it was painted and evidently well respected because, shortly after its completion, he was elected Prior of the Collegio dei Pittori: a position which he continued to hold until he was made the first Director of the newly founded Venetian State Academy in 1750. Artistic outsider he might have been in some respects, but this did not preclude official recognition. The Martyrdom of Saint James is a summation of what we can glean of his earlier career. It follows on naturally from his first public commission, very probably in 1718, to paint an altarpiece of the Madonna with a Guardian Angel for the Scuola del Angelo Custode: an altarpiece, according to D’Argenville, that was ‘le premier tableau considerable qu’il fit’ (the first considerable painting that he made).

This survives in a fragmentary state in the Detroit Institute of Arts and the bozzetto is in the Los Angeles County Museum. This commission was clouded with controversy because the Scuola refused to pay Piazzetta’s asking price of 100 zecchini and he therefore sold the picture at the San Rocco fair for 130 zecchini, more than the fee paid to Sebastiano Ricci by the Scuola for a substitute altarpiece. This showed that Piazzetta’s work had considerable value on the open market, but must have soured relations between the artist and his first important institutional patron. In between the execution of that altarpiece and the Martyrdom of Saint James are a group of tenebrist works which have been assigned on stylistic grounds to the late 1710s, such as the Susanna and the Elders (Uffizi Gallery, Florence), The Sacrifice of Abraham (Baroda Picture Gallery, India) and the Rape of Helen (Musee Granet, Aix en Provence), which show the same combination of Caravaggesque lighting, dynamic movement and powerful realism as in the Martyrdom, fusing influences from Crespi, Guercino and Solimena overlaid on the foundations of late Baroque artists working in Venice such as Zanchi, Loth and Bencovich.

The Scuola del Angelo Custode altarpiece reveals the meticulousness of Piazzetta’s working methods, starting often with preparatory drawings and a swiftly executed oil sketch, which would then be developed through a larger and much more fully worked out modello to the final work. Unlike Tiepolo, who, according to the Swedish collector Count Tessin, ‘executes a picture, while another person has hardly mixed the colours’, Piazzetta was, according to the Count, ‘a snail’ (at least when it came to his finished paintings). It is therefore through the bozzetti, like the present lively example, that we can best glean an understanding of the working methods of this most thoughtful of artists.

In our bozzetto, the brutality of the executioner and his well-muscled body comes over even more strongly than in the finished painting. Likewise, the contrast of light and dark is even more marked than in the San Stae canvas. The saint’s proper right foot, which is cast in shadow in the left-hand side of the large canvas, is here brilliantly spot lit, and one can observe the tension in the toes clinging precariously to the slope while the ghostly figure of the horseman in the background, who is riding to join the execution party, is given greater prominence, heightening the sense of drama and foreboding.

However, the sketch also shows the more linear composition of the artist’s first idea, with the saint’s captor grasping at his clothing from behind shown in full profile, which is then modulated in the final composition through the introduction of the rope: a brilliant leitmotif which provides the fulcrum for the more swinging rhythm of the artist’s final solution, creating greater fluidity and dynamism which is emphasized by the turning of the guard’s head in profil perdu rather than full profile.

The sketch, which provides the key to understanding how this complex composition evolved, was in the well-known Venetian collection of Italico Brass, which included several other paintings by Piazzetta, and was lent anonymously to an exhibition in Baltimore in 1968. In his catalogue essay, Roger Rearick wrote that ‘among his playful contemporaries, Piazzetta strikes a note of sombre grandeur’, and notes that ‘for almost forty years [he] remained a firm outpost of the baroque amid the growing frivolity of Venice’.[xi]

When he died at the age of 71 in 1750, he was, as Rearick wrote, a ‘relic of a then remote era’, and he was largely forgotten throughout the nineteenth century. Only in recent times has Piazzetta been recognised as a Venetian eighteenth-century artist who was second only in importance to Tiepolo, even if his art was very different, and he was arguably, as Binion has observed, ‘Caravaggio’s last great disciple even if that designation fails to describe him in full’.[xii]

He was also an artist who, as Binion argued again, had much in common with Rembrandt: an artist much admired in eighteenth-century Venice.[xiii]

The present sketch – the only surviving one connected with the San Stae series – affords a rare insight into the gestation of one of Piazzetta’s most important and seminal works.

[i] G. Knox, Giambattista Piazzetta (1682 – 1754), Oxford 1992, p. 95.

[ii] L. Moretti, ‘La data degli apostoli della chiesa di San Stae’, Arte Veneta, no. XXVII, 1973, pp. 318-20.

[iii] In alphabetical order: Antonio Balestra, Nicolò Bambini, Gregorio Lazzarini, Silvestro Manaigo, Giambattista Mariotti, Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini, Giambattista Piazzetta, Giambattista Pittoni, Sebastiano Ricci, Giambattista Tiepolo, Angelo Trevisano and Pietro Uberti.

[iv] According to D. Ton, in Tiepolo: Venezia, Milano, l'Europa, exh. cat., (eds.) F. Mazzocca & A. Morandotti, Milan 2020, p. 176, under cat. no. 25.

[v] See L. Jones, The Paintings of Giovanni Battista Piazzetta, Ann Arbor 1981, ii, 203 (22).

[vi] The fact that Pellegrini had left Venice by May 1722 is strong evidence that his painting of the Crucifixion of Saint Andrew was part of the first phase.

[vii] M. Levey, Giambattista Tiepolo: His Life and Art, New Haven 1986, p. 12.

[viii] M. Levey, Painting in Eighteenth Century Venice, Oxford 1980, p. 59.

[ix] Knox 1992, p. 97.

[x] A. Binion, ‘The Piazzetta Paradox’, in The Glory of Venice: Art in the Eighteenth Century, exh. cat., (eds.) J. Martineau & A. Robison, New Haven 1994, p. 150.

[xi] R. Rearick, in From El Greco to Pollock: Early and late works by European and American artists, exh. cat., (ed.) G. Rosenthal, Baltimore 1968, p. 57.

[xii] Binion 1994, p. 139.

[xiii] Binion 1994, p. 167.