Palazzo Fantuzzi, Bologna;

Private collection, Italy.

P. Tosini, Girolamo Muziano: The Saint Jerome in the Wilderness rediscovered, With new additions to the Catalogue Raisonné, (trans.) F. Nevola, Rome 2019, pp. 2-20, 25, 36-39, cat. no. A4, figs. 2, 5, 8, 9, 12, reproduced in colour.

Click here to download the factsheet

This recently rediscovered altarpiece, first published in 2019, is a notable addition to the corpus of the Brescian painter Girolamo Muziano, one of the leading artists working in Rome and Bologna during the later sixteenth century. As official painter to Pope Gregory XIII, Muziano’s contemporary fame was such that King Phillip II of Spain’s Ambassador to the Holy See, Juan de Zuñiga, singled him out in 1577 as one of the two most esteemed artists in Rome along with Marcello Venusti.[i] Muziano was also active in the pope’s home town of Bologna where, according to an anonymous biographer, he painted ‘many fine things – paintings and altarpieces’, playing an important role as a link between late Mannerism and the early development of the Baroque in Bologna which was spearheaded in the 1580s by the Carracci. His art was notable for a spiritual intensity in line with the teachings of the Counter-Reformation Church and the beauty and naturalism of the landscape backgrounds, whose vivid colouring and handling of light, seen in the striking rosy sky of the present Saint Jerome, owe much to Muziano’s early contact with Venetian art, as well as with the lyrical landscapes of Muziano’s Brescian compatriot Girolamo Savoldo and the paintings of Domenico Campagnola and Lambert Sustris, which he encountered as a young artist in Padua.

Our painting is closely related to Muziano’s slightly larger Saint Jerome in the Wilderness altarpiece now in the Pinacoteca Nazionale, Bologna, the only Bolognese altarpiece by him for which we have a certain provenance.

This painting entered the museum’s collections following the Napoleonic suppression of the religious orders in 1797. The picture hung in the Pasi Chapel in the Servite Church of San Giorgio Poggiale, Bologna, throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, but it’s earlier history is not known. Seemingly it did not enter the chapel until at the earliest 1625, when the space was granted to that notable art-lover and close friend of Domenichino’s, Giovanni Battista Agucchi, on the condition that he honour and adorn it appropriately. It was likely that the Bologna altarpiece was among the adornments introduced by Agucchi around that time and it was certainly there by 1686, when it was recorded in Malvasia’s guidebook, Pitture di Bologna.[ii]

The present picture is very similar in composition to the altarpiece in the Pinacoteca Nazionale, but the presence of numerous pentimenti leaves no doubt that it is an original autograph work of the highest quality, a ‘splendid and closely related version’ according to Tosini, in which there are subtle but significant differences, which are discussed below.[iii] Moreover, whereas the Bologna altarpiece has suffered several losses, the superb condition of our picture enables an appreciation of the vibrant colouring and beautiful landscape background for which Muziano, dubbed by Baglione as the ‘giovane dei paesi’ (the youth of landscapes), was so celebrated in his own day. Its provenance suggests that it, like the Saint Jerome altarpiece in the Pinacoteca, was one of the ‘many things – paintings and altarpieces’ with which, according to his first biographer,[iv] he adorned the Emilian capital.

Early History

Although the early provenance of our picture cannot be definitively established, it was likely painted for a Bolognese patron during the early 1570s, around the same time as the altarpiece in the Pinacoteca Nazionale. According to Tosini, there are several early references to a painting or paintings in Bologna which could be linked to our picture. The first, included within the manuscript guide of 1603 by the painter Francesco Cavazzoni, describes a ‘large painting with the figure of S. Jeronimo by the hand of Mutiano [sic.] a very beautiful work’ which is listed as being at the house of Senator Fantuzzi:[v] the Palazzo Fantuzzi in Via San Vitale, Bologna. There are several later references in the inventories of the Palazzo Fantuzzi to paintings representing Saint Jerome, though unfortunately with no dimensions given or indications of authorship, however, what is very likely the same picture as that recorded by Cavazzoni resurfaced in Marcello Oretti’s manuscript guide (c. 1769) of the picture collections in the palaces and houses of the Bolognese nobility, Le Pitture che si ammirano nelle Palaggi e Case dei Nobili della Citta di Bologna,[vi] where the picture was listed in the Palazzo Fantuzzi. Since at that time the altarpiece formerly in the Bologna Pinacoteca was still in situ in the Pasi Chapel, this cannot be the picture referred to, though the fact that a ‘large painting’ is described suggests that it must have been an altarpiece and its size certainly accords with that of the present picture. Cavazzoni’s is not only the oldest, but also the most reliable reference that we have that might give a clue to the early provenance of our picture, written as it was only a few years after Muziano’s death by an artist who had served as a page to the Fantuzzi family. In the 1670s Malvasia recalled how Cavazzoni was ‘placed at the age of twelve as a page to Signor Carlo Fantuzzi, the descendant of that Fantuzzi who was such a friend to painters and, because he had a small Nativity by Raphael, a St Jerome by Muziano, four paintings by Bassano and others similar, the youth had set himself to copy them in pen and, when asked by his master whether he would like to become a painter, being answered in the affirmative, he was taken to Annibale Carracci’.[vii]

What was probably a third version of a Saint Jerome in the Desert by Muziano was recorded in 1740 in an inventory of the Bianchetti Collection, Bologna. Given that Ludovico Bianchetti was ‘cubiculario’ (custodian of the bedchamber) to Muziano’s greatest patron, Pope Gregory XIII, and himself a patron of the artist, it is likely that he would have commissioned this painting for his family house in Bologna and the subject of one of the Fathers of the Church would have had obvious appeal to a high-ranking Bolognese prelate in the papal entourage, although it is impossible to tell whether this was an altarpiece or, as would have been more likely in a domestic setting, a smaller devotional picture. Finally, there is mention of a ‘St Jerome by Mucciano’ in an inventory of 1689 of the chattels belonging to Giovanni Francesco Negri, but again with no indication of dimensions. Of the pictures referred to above, the one most likely to be identifiable as our picture, given its size, is that formerly in the Palazzo Fantuzzi in Bologna and, if this identification is correct, then our Saint Jerome would have very likely been the ‘St Jerome by Muziano’ mentioned by Malvasia, which was copied by the young Cavazzoni while he was a page in the Fantuzzi household.

Genesis, Style and Technique

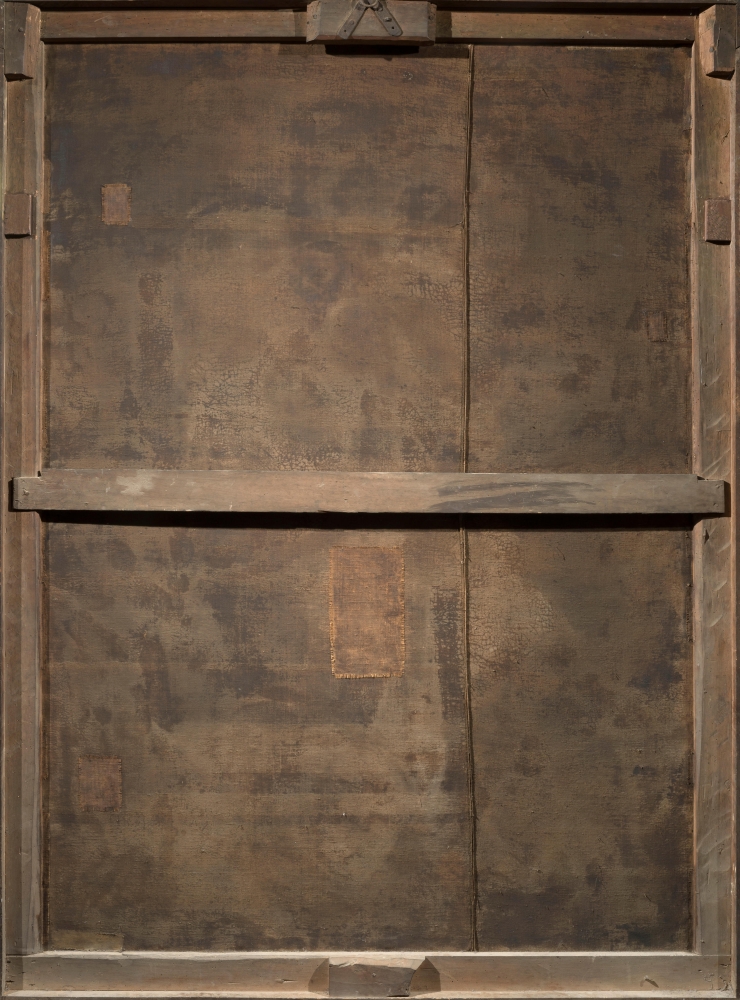

Returning now to the two principal versions of the subject – the one in the Pinacoteca in Bologna and the present picture – the close affinities in style and subject matter suggest that both were painted around the same time, probably, suggests Tosini, in the early 1570s. The present picture is slightly smaller and more intimate than the Bologna Pinacoteca version and, unlike that version, which has suffered from old and careless restorations, is in a remarkable state of preservation. It is still supported by its original canvas, mounted on a separate stretcher but fully integrated within the original seventeenth-century frame, which is an extremely rare survival. This makes it possible to appreciate more fully than is the case with the Bologna picture, Muziano’s extraordinary interplay of light and colour and provides valuable clues to the picture’s dating. There are, for example, close correspondences between our picture and others made shortly after Pope Gregory’s ascent to the papal throne in 1572, such as the two large canvasses executed in 1573-4 for the side walls of the chapel for the banker Giovanni Battista Altoviti, now in the Museo della Santa Casa, Loreto, which include figures characterised by a Michelangelesque muscularity in their bodies and a powerful expressiveness in the heads, found also in our figure of Saint Jerome. Similar qualities can also be found in the slightly earlier figure by Muziano of Saint Jerome at Prayer, painted by the artist for the Ruiz Chapel of Santa Caterina dei Funari in Rome between 1566 and 1568, where the hermit saint leans towards a crucifix on a rocky ledge silhouetted against a stormy sky, and the lion at his feet is clearly drawn from the same model as in our picture.

The head of our saint has parallels with that of a prophet in the Altoviti chapel canvasses, both being ‘poised’, as Tosini observes, ‘between being ‘taken from life’ and ideally ennobled’,[viii] a stylistic fusion which anticipates the work of Ludovico and Annibale Carracci in the 1580s. But the closest relationship is with the study for the head of a Prophet, now in the Rijksmuseum, drawn twenty years earlier in connection with the frescoes of 1552-3 in Santa Catarina della Rota in Rome, his first independent public commission. The head of our Saint Jerome seems to be taken from the same model.

The Santa Catarina frescoes were, as Tosini observes, ‘painted when the experience of his Venetian sojourn was still fresh’.[ix] The choice of blue paper for the preparatory drawing is also typically Venetian, and the rather broader and more atmospheric rendering of the saint’s head, when compared to that of the more defined figure of the prophet from the Altoviti chapel, suggests that here the artist was drawing upon earlier sources of artistic inspiration. The combination of cobalt blue and sunset pink tones in the sky and the wild setting in which the saint is immersed, seen also in the background of Muziano’s Raising of Lazarus in the Birmingham City Museum and Art Gallery, also recall the artist’s Venetian experience, while the trees, intertwined in figures of eight are, as Tosini observes, trademark features of his art. There are also elements within the landscape – in the cold colours and scintillating light on the trees – which have strong affinities with the work of the Flemish artists Matthijs and his more famous brother Paul Bril who, according to Baglione, knew and admired Muziano’s work. This shows how Muziano influenced Flemish artists as he, in turn, had been influenced by the landscapes of Lambert Sustris earlier in his career. The combination of Venetian colouring and landscape background and the Michelangelesque figure of the saint is a typically eclectic fusion which anticipates later trends in Bolognese art.

The variations between our picture and the altarpiece in the Pinacoteca are few but significant. These include the rocky arch, fully closed in the Pinacoteca version but slightly open in our picture, which is clearly influenced by Titian’s Saint Jerome in the Wilderness in the Escorial.

The traditional iconography of Saint Jerome veers between two typologies: that of the scholar saint in his study (seen, perhaps most famously, in Durer’s celebrated woodcut), or the ascetic penitent saint beating his breast with a rock, as in Cosimo Tura’s wild depiction of Saint Jerome in a rocky landscape in the National Gallery, London. The two versions of the Saint Jerome altarpiece incorporate both aspects of this typology, but the figure of the saint in the Bologna Pinacoteca painting is more extravagantly penitential and ascetic, with his bare torso and relatively simple tunic covering his lap, whereas our saint with his rich pink and blue robes and the bible on his knee is presented in a more refined and meditative way. The more compressed composition of our picture gives it a greater degree of intimacy, with the lion moved companionably closer to the saint. The saint has also been placed closer to the crucifix, which is seen more directly at eye level rather than from below, stressing inward meditation rather than outward penitence. The comparative refinement of our picture is reflected in the beautiful detailing of the ivy, which is shown growing up the rock below the crucifix. One recurring feature in Muziano’s work which is seen here is the rendering of the crucifix before the hermit, which is seen at an angle from the rear, as in the Hermit Saint in the Vatican Picture Gallery.

All the adjustments noted above have the effect of emphasizing, as Tosini observes ‘an intimate connection between the saint and the crucifix’.

Both the draughtsmanship and the brushwork in our Saint Jerome reveal the impact of Muziano’s early encounter with the work of Lambert Sustris and Domenico Campagnola in Padua, through whom he imbibed the traditions of Venetian painting. The handling of the paint is notable for its fluidity and also for the variety of techniques employed: ‘almost dripping in the landscape and passages of verdure; it is transparent and fine for the depiction of rock and … precise and substantial for the definition of the figure’.[x] This has the effect of making the figure seem to emerge forcefully from its background.

Muziano made a magnificent study for the figure of Saint Jerome which is now in the Louvre, in which, unlike in our painting, the head of the saint is tilted back with his eyes raised imploringly towards Heaven. This drawing belonged at one time to Rubens, who was a great admirer of Muziano’s drawings, and this provided the inspiration for a Rubens drawing, now in the Morgan Library, in which Rubens has exactly borrowed the clasped hand gesture of Saint Jerome and the precise twist of the body, gesture of the arms and arrangements of the legs, while the aged head of the eremitic saint has been replaced by that of a beardless youth. This, in turn, provided the model for Rubens’s painting of Daniel in the Lion’s Den in the National Gallery of Art, Washington.

Further indications of the influence of Muziano’s Saint Jerome compositions are to be found in two prints by Cornelis Cort from his celebrated series of Hermits in a Landscape, engraved in 1573 after the drawings by Muziano showing saints in a forest. This novel type of presentation was to have influence well beyond the Counter Reformation, into the seventeenth century. One of these prints, which is closest to the Bologna Pinacoteca altarpiece, shows the semi-naked saint with clasped hands and adoring a crucifix, which, as in both of the painted altarpieces, is seen from behind; another, closer to the present altarpiece, shows the saint in the guise of a hermit, accompanied by a lion, translating the Bible with a book on his knee. This in turn provided the impetus for a series of paintings of hermits which Muziano made for some of his most prestigious Bolognese patrons: members of the Fantuzzi, Boncompagni and Bianchetti families, and exercised a profound influence on later Bolognese artists such as Annibale and Ludovico Carracci, seen, for example, in Ludovico’s Saint Francis (Pinacoteca Capitolina, Rome), where the ideas are based on compositional solutions deriving from Muziano.

Biography

Muziano was born in Brescia in 1528/32 and was influenced by the work of his compatriot Girolamo Savoldo. Between 1544 and 1546, Muziano was resident in Padua where, despite being only in his early teens, he imbibed the influences, crucial for the development of his later pictorial language, of Lambert Sustris and Domenico Campagnola. He spent the next four years (1546 – 1550) in Venice and in 1548 is recorded working at the Villa Barbaro in Maser alongside Battista Ponchino, an artist in the entourage of the Grimani. During this early period in Venice, Muziano was to be greatly influenced by the religious paintings of Titian and the early work of Tintoretto. His contacts with the Grimani and Barbaro families may have provided him with an entrée to patrons in Rome, where he moved in 1549, and this was to be the main centre of his activities for the rest of his career, although he seems to have returned quite frequently to Venice where his brother had a business manufacturing armour.

In Rome he quickly acquired a reputation as a talented young artist, particularly admired for his landscape paintings; his first Roman works were to provide landscape backgrounds to the frescoes by Battista Franco in the Contarelli Chapel of Santa Maria sopra Minerva (1550) and some lost landscape frescoes in the Sala della Cleopatra of the Vatican Belvedere (1551-2) where he worked alongside Daniele da Volterra, who was probably his first Roman master. Muziano’s first independent public work was the Flight into Egypt (1552-3) in Santa Caterina della Rota, for which one of his preparatory drawings (discussed above) was to provide the head of Saint Jerome in the present altarpiece. Landscape remained a dominant theme in the cycle of frescoes of Ovid’s Metamorphoses painted for the Castle of Giuliano Cesarini at Rocca Sinibalda where he introduced notably Venetian elements into landscapes inspired by the Roman Campagna, showing an evident debt to Lambert Sustris’s interiors for the Villa dei Vescovi near Padua. Muziano’s Roman breakthrough came with the commission for a vast canvas of the Raising of Lazarus (now in the Pinacoteca Vaticana) which hung for a time in the Palazzo Venezia, Rome, where it attracted the admiration of Michelangelo and the sculptor and architect Raffaello del Montelupo. Through Montelupo Muziano secured a commission to work at Orvieto Cathedral, contributing paintings of the Raising of Lazarus and Ascent to Calvary to a cycle representing the miracles of Christ, which was seminal to the development of Post-Tridentine painting in the Papal States.

On his return to Rome in 1560, Muziano’s career took off when he became court painter to Cardinal Ippolito II d’Este, for whom he worked both in the Cardinal’s Roman palazzi and on the decoration of the Villa d’Este at Tivoli. Five years later, in 1565, Muziano was married and in the following year embarked upon an important cycle of canvasses of the Miracles of Christ for the Ruiz Chapel in Santa Caterina, in Rome, which are among his most admired works. From about 1550 Muziano developed profitable relationships with engravers, notably Cornelis Cort and Nicolas Beatrizet with whom he collaborated on a famous series of prints of hermits (discussed above). The election of Ugo Boncompagni as Pope Gregory XIII saw Muziano established as painter to the leading members of the papal Curia, and it was during the 1570s that he painted some of his most ambitious works such as the high altar paintings in San Luigi dei Francesi and the magnificent altarpiece of the Crucifixion commissioned by the Pope for the Capuchin church at Frascati. In 1578 these achievements were crowned by his appointment as a provisionato of the Pope, receiving a monthly salary to serve as superintendent of all papal art enterprises. These included supervising the decoration of the Galleria delle Carte Geografiche in the Vatican. The death of Pope Gregory in 1585 and the beginning of the reign of his successor, Sixtus V, brought to a close Muziano’s brilliant career as he found himself increasingly marginalised, although he did produce an excellent series of late frescoes of the Stories of Saint Matthew for the Chapel of Ciriaco Mattei at the Arcoeli, which were remarkable for their austere classicism.

Conclusion

The present altarpiece of Saint Jerome, painted when the artist was at the height of his artistic powers as the leading painter working at the papal court and receiving important commissions from Bolognese patrons, is an important rediscovery. Notable for its immaculate condition and vibrant colouring, the picture both looks back to the work of the great Venetian artists who inspired the youthful Muziano and points forward to the art of the Carracci and the onset of the Baroque at the end of the sixteenth century. The figure of our Saint Jerome was also to inspire Rubens’s Daniel in the Lion’s Den and, through the medium of de Cort’s prints of 1573 of hermit saints in wild wooded landscapes, inspired later artists such as Salvator Rosa and Velazquez, all of whom, in varying ways, were drawing upon mid-sixteenth century developments that can be seen in the art of Muziano and his contemporaries.

Footnotes

[i] Cited by R. Mulcahy, in Philip II of Spain, Patron of the Arts, Dublin 2004, p. 42.

[ii] For a summary of the history of the altarpiece now in the Bologna Pinacoteca Nazionale, see P. Tosini, in Pinacoteca Nazionale di Bologna, Venice 2006, pp. 357-9 and P. Tosini, Girolamo Muziano 1532-1592. Dalla Maniera alla Natura, Rome 2008, pp. 367-9, cat. no. A17.

[iii] P. Tosini, Girolamo Muziano: The Saint Jerome in the Wilderness rediscovered, With new additions to the Catalogue Raisonné, (trans.) F. Nevola, Rome 2019, pp. 3 & 11.

[iv] See U. Procacci, ‘Una vita inedita di Girolamo Muziano’, Arte Veneta, 8, 1954, pp. 242-264. Procacci’s article is based on an anonymous manuscript of the mid 1580s written by Muziano’s confessor.

[v] E. Calbi & D. Scaglietti Kelescian, ‘Marcello Oretti e il patrimonio artistico privato Bolognese’, Bologna, Biblioteca Comunale, Ms. B. 104, Istituto per i beni artistici culturali naturali della Regione Emilia-Romana,

Documenti, 22, 1984, p. 142; Tosini 2019, p. 6.

[vi] Calbi & Scaglietti Kelescian 1984, loc. cit.

[vii] C. C. Malvasia, Felsina Pittrice. Vite dei pittori Bolognese, Bologna 1678, republished in 1848, II, p. 146, quoted by Tosini 2019, p. 6.

[viii] Tosini 2019, p. 9.

[ix] Tosini 2019, p. 10.

[x] Tosini 2019, p. 16.